Binomial theorem

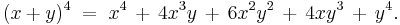

In elementary algebra, the binomial theorem describes the algebraic expansion of powers of a binomial. According to the theorem, it is possible to expand the power (x + y)n into a sum involving terms of the form axbyc, where the coefficient of each term is a positive integer, and the sum of the exponents of x and y in each term is n. For example,

The coefficients appearing in the binomial expansion are known as binomial coefficients. They are the same as the entries of Pascal's triangle, and can be determined by a simple formula involving factorials. These numbers also arise in combinatorics, where the coefficient of xn−kyk is equal to the number of different combinations of k elements that can be chosen from an n-element set.

Contents |

History

This formula and the triangular arrangement of the binomial coefficients are often attributed to Blaise Pascal, who described them in the 17th century, but they were known to many mathematicians who preceded him. The 4th century B.C. Greek mathematician Euclid mentioned the special case of the binomial theorem for exponent 2[1][2] as did the 3rd century B.C. Indian mathematician Pingala to higher orders. A more general binomial theorem and the so-called "Pascal's triangle" were known in the 10th-century A.D. to Indian mathematician Halayudha and Persian mathematician Al-Karaji,[3] and in the 13th century to Chinese mathematician Yang Hui, who all derived similar results.[4] Al-Karaji also provided a mathematical proof of both the binomial theorem and Pascal's triangle, using mathematical induction.[3]

Statement of the theorem

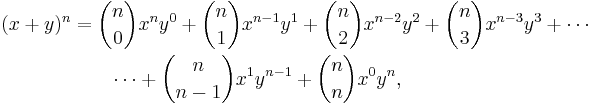

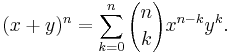

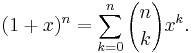

According to the theorem, it is possible to expand any power of x + y into a sum of the form

where  denotes the corresponding binomial coefficient. Using summation notation, the formula above can be written

denotes the corresponding binomial coefficient. Using summation notation, the formula above can be written

This formula is sometimes referred to as the binomial formula or the binomial identity.

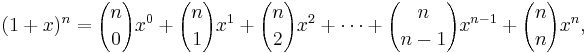

A variant of the binomial formula is obtained by substituting 1 for x and x for y, so that it involves only a single variable. In this form, the formula reads

or equivalently

Examples

The most basic example of the binomial theorem is the formula for square of x + y:

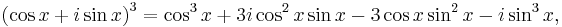

The binomial coefficients 1, 2, 1 appearing in this expansion correspond to the third row of Pascal's triangle. The coefficients of higher powers of x + y correspond to later rows of the triangle:

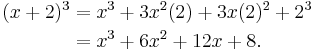

The binomial theorem can be applied to the powers of any binomial. For example,

For a binomial involving subtraction, the theorem can be applied as long as the negation of the second term is used. This has the effect of negating every other term of the expansion:

Geometrical explanation

For positive values of a and b, the binomial theorem with n = 2 is the geometrically evident fact that a square of side a + b can be cut into a square of side a, a square of side b, and two rectangles with sides a and b. With n = 3, the theorem states that a cube of side a + b can be cut into a cube of side a, a cube of side b, three a×a×b rectangular boxes, and three a×b×b rectangular boxes.

The binomial coefficients

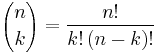

The coefficients that appear in the binomial expansion are called binomial coefficients. These are usually written  , and pronounced “n choose k”.

, and pronounced “n choose k”.

Formulas

The coefficient of xn−kyk is given by the formula

which is defined in terms of the factorial function n!. Equivalently, this formula can be written

with k factors in both the numerator and denominator of the fraction. Note that, although this formula involves a fraction, the binomial coefficient  is actually an integer.

is actually an integer.

Combinatorial interpretation

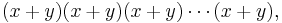

The binomial coefficient  can be interpreted as the number of ways to choose k elements from an n-element set. This is related to binomials for the following reason: if we write (x + y)n as a product

can be interpreted as the number of ways to choose k elements from an n-element set. This is related to binomials for the following reason: if we write (x + y)n as a product

then, according to the distributive law, there will be one term in the expansion for each choice of either x or y from each of the binomials of the product. For example, there will only be one term xn, corresponding to choosing 'x from each binomial. However, there will be several terms of the form xn−2y2, one for each way of choosing exactly two binomials to contribute a y. Therefore, after combining like terms, the coefficient of xn−2y2 will be equal to the number of ways to choose exactly 2 elements from an n-element set.

Proofs

Combinatorial proof

Example

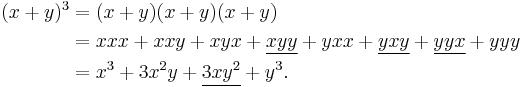

The coefficient of xy2 in

equals  because there are three x,y strings of length 3 with exactly two y's, namely,

because there are three x,y strings of length 3 with exactly two y's, namely,

corresponding to the three 2-element subsets of { 1, 2, 3 }, namely,

where each subset specifies the positions of the y in a corresponding string.

General case

Expanding (x + y)n yields the sum of the 2 n products of the form e1e2 ... e n where each e i is x or y. Rearranging factors shows that each product equals xn−kyk for some k between 0 and n. For a given k, the following are proved equal in succession:

- the number of copies of xn − kyk in the expansion

- the number of n-character x,y strings having y in exactly k positions

- the number of k-element subsets of { 1, 2, ..., n}

(this is either by definition, or by a short combinatorial argument if one is defining

(this is either by definition, or by a short combinatorial argument if one is defining  as

as  ).

).

This proves the binomial theorem.

Inductive proof

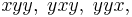

Induction yields another proof of the binomial theorem (1). When n = 0, both sides equal 1, since x0 = 1 for all x and  . Now suppose that (1) holds for a given n; we will prove it for n + 1. For j, k ≥ 0, let [ƒ(x, y)] jk denote the coefficient of xjyk in the polynomial ƒ(x, y). By the inductive hypothesis, (x + y)n is a polynomial in x and y such that [(x + y)n] jk is

. Now suppose that (1) holds for a given n; we will prove it for n + 1. For j, k ≥ 0, let [ƒ(x, y)] jk denote the coefficient of xjyk in the polynomial ƒ(x, y). By the inductive hypothesis, (x + y)n is a polynomial in x and y such that [(x + y)n] jk is  if j + k = n, and 0 otherwise. The identity

if j + k = n, and 0 otherwise. The identity

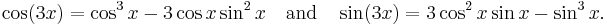

shows that (x + y)n+1 also is a polynomial in x and y, and

If j + k = n + 1, then (j − 1) + k = n and j + (k − 1) = n, so the right hand side is

by Pascal's identity. On the other hand, if j +k ≠ n + 1, then (j – 1) + k ≠ n and j +(k – 1) ≠ n, so we get 0 + 0 = 0. Thus

and this completes the inductive step.

Generalizations

Newton's generalized binomial theorem

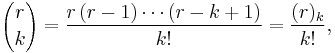

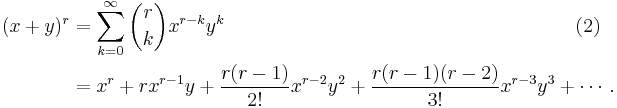

Around 1665, Isaac Newton generalized the formula to allow real exponents other than nonnegative integers, and in fact it can be generalized further, to complex exponents. In this generalization, the finite sum is replaced by an infinite series. In order to do this one needs to give meaning to binomial coefficients with an arbitrary upper index, which cannot be done using the above formula with factorials; however factoring out (n−k)! from numerator and denominator in that formula, and replacing n by r which now stands for an arbitrary number, one can define

where  is the Pochhammer symbol here standing for a falling factorial. Then, if x and y are real numbers with |x| > |y|,[5] and r is any complex number, one has

is the Pochhammer symbol here standing for a falling factorial. Then, if x and y are real numbers with |x| > |y|,[5] and r is any complex number, one has

When r is a nonnegative integer, the binomial coefficients for k > r are zero, so (2) specializes to (1), and there are at most r + 1 nonzero terms. For other values of r, the series (2) has an infinite number of nonzero terms, at least if x and y are nonzero.

This is important when one is working with infinite series and would like to represent them in terms of generalized hypergeometric functions.

Taking r = −s leads to a particularly handy but non-obvious formula:

Further specializing to s = 1 yields the geometric series formula.

Generalizations

Formula (2) can be generalized to the case where x and y are complex numbers. For this version, one should assume |x| > |y|[5] and define the powers of x + y and x using a holomorphic branch of log defined on an open disk of radius |x| centered at x.

Formula (2) is valid also for elements x and y of a Banach algebra as long as xy = yx, x is invertible, and ||y/x|| < 1.

The multinomial theorem

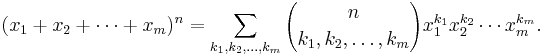

The binomial theorem can be generalized to include powers of sums with more than two terms. The general version is

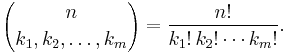

where the summation is taken over all sequences of nonnegative integer indices k1 through km such the sum of all ki is n. (For each term in the expansion, the exponents must add up to n). The coefficients  are known as multinomial coefficients, and can be computed by the formula

are known as multinomial coefficients, and can be computed by the formula

Combinatorially, the multinomial coefficient  counts the number of different ways to partition an n-element set into disjoint subsets of sizes k1, ..., kn.

counts the number of different ways to partition an n-element set into disjoint subsets of sizes k1, ..., kn.

Applications

Multiple angle identities

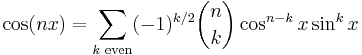

The binomial theorem can be combined with De Moivre's formula to yield multiple-angle formulas for the sine and cosine. According to De Moivre's formula,

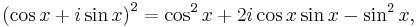

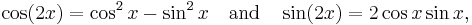

Using the binomial theorem, the expression on the right can be expanded, and then the real and imaginary parts can be taken to yield formulas for cos(nx) and sin(nx). For example, since

De Moivre's formula tells us that

which are the usual double-angle identities. Similarly, since

De Moivre's formula yields

In general,

and

Series for e

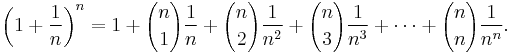

The number e is often defined by the formula

Applying the binomial theorem to this expression yields the usual infinite series for e. In particular:

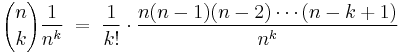

The kth term of this sum is

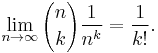

As n → ∞, the rational expression on the right approaches one, and therefore

This indicates that e can be written as a series:

Indeed, since each term of the binomial expansion is an increasing function of n, it follows from the monotone convergence theorem for series that the sum of this infinite series is equal to e.

The binomial theorem in abstract algebra

Formula (1) is valid more generally for any elements x and y of a semiring satisfying xy = yx. The theorem is true even more generally: alternativity suffices in place of associativity.

The binomial theorem can be stated by saying that the polynomial sequence { 1, x, x2, x3, ... } is of binomial type.

See also

- Binomial distribution

- Binomial probability

- Binomial inverse theorem

- Binomial series

- Combination

- Stirling's approximation

- Multinomial theorem

- Negative binomial distribution

- Pascal's triangle

- Binomial approximation

Notes

- ↑ Binomial Theorem

- ↑ The Story of the Binomial Theorem, by J. L. Coolidge, The American Mathematical Monthly 56:3 (1949), pp. 147–157

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Abu Bekr ibn Muhammad ibn al-Husayn Al-Karaji", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Al-Karaji.html.

- ↑ Landau, James A (1999-05-08). "Historia Matematica Mailing List Archive: Re: [HM] Pascal's Triangle" (mailing list email). Archives of Historia Matematica. http://archives.math.utk.edu/hypermail/historia/may99/0073.html. Retrieved 2007-04-13.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 This is to guarantee convergence. Depending on r, the series may also converge sometimes when |x| = |y|.

References

- Bag, Amulya Kumar (1966). "Binomial theorem in ancient India". Indian J. History Sci 1 (1): 68–74.

- Graham, Ronald; Donald Knuth, Oren Patashnik (1994). "(5) Binomial Coefficients". Concrete Matehamtics (2nd ed.). Addison Wesley. pp. 153–256. ISBN 0-201-55802-5. OCLC 17649857.

- Solomentsev, E.D. (2001), "Newton binomial", in Hazewinkel, Michiel, Encyclopaedia of Mathematics, Springer, ISBN 978-1556080104, http://eom.springer.de/n/n066500.htm

External links

- Binomial Theorem by Stephen Wolfram, and "Binomial Theorem (Step-by-Step)" by Bruce Colletti and Jeff Bryant, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

This article incorporates material from inductive proof of binomial theorem on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

![\begin{align}

(x+y)^3 & = x^3 + 3x^2y + 3xy^2 + y^3, \\[8pt]

(x+y)^4 & = x^4 + 4x^3y + 6x^2y^2 + 4xy^3 + y^4, \\[8pt]

(x+y)^5 & = x^5 + 5x^4y + 10x^3y^2 + 10x^2y^3 + 5xy^4 + y^5, \\[8pt]

(x+y)^6 & = x^6 + 6x^5y + 15x^4y^2 + 20x^3y^3 + 15x^2y^4 + 6xy^5 + y^6, \\[8pt]

(x+y)^7 & = x^7 + 7x^6y + 21x^5y^2 + 35x^4y^3 + 35x^3y^4 + 21x^2y^5 + 7xy^6 + y^7.

\end{align}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/05912cb66ba1a0cc47688071d5cdae8a.png)

![[(x+y)^{n+1}]_{jk} = [(x+y)^n]_{j-1,k} + [(x+y)^n]_{j,k-1}. \,](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/7e1705a0868645bb42809f3cb58980de.png)